Editor's Note: Below is an excerpt from a review originally published in Halo Halo Review.

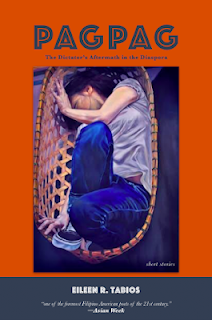

It’s an unfortunate and ugly reality that many people in the homeland are so destitute, so poor, that they make a necessary living out of garbage. The practice of “pagpag” involves going through mountains of trash to salvage food and anything else than can be saved to be resold, reused, or traded for other goods. Eileen Tabios’ explains that her latest short story collection, PAGPAG, is so named to shed light on the ever-increasing economic inequities among the urban poor in the Philippines, casualties of decades-long theft, graft and corruption among elected officials and their cronies.

The stories in PAGPAG offer insights to the process of reconstituting a salvaged and made-new life after expulsion, making the most out of the refuse of life in the diaspora. In the book’s introduction, Tabios specifically calls out the Marcos dictatorship for the harms caused to Filipinos who fled the country to escape the violence and turmoil of the Martial Law era (1972-1986), as well as the torment endured by millions of Filipinos who had little choice but stay behind. The author was a child when her family escaped the talons of martial law under the Marcos regime. She draws a link between the damages wrought by the Marcos regime to the renewed clamor for strongman-style leadership that led to the election of Rodrigo Duterte in 2016. The dictator not only ransacked the treasury, he also drove away the collective memory about the painful truths of those difficult and repressive years.

Read the full review

It’s an unfortunate and ugly reality that many people in the homeland are so destitute, so poor, that they make a necessary living out of garbage. The practice of “pagpag” involves going through mountains of trash to salvage food and anything else than can be saved to be resold, reused, or traded for other goods. Eileen Tabios’ explains that her latest short story collection, PAGPAG, is so named to shed light on the ever-increasing economic inequities among the urban poor in the Philippines, casualties of decades-long theft, graft and corruption among elected officials and their cronies.

The stories in PAGPAG offer insights to the process of reconstituting a salvaged and made-new life after expulsion, making the most out of the refuse of life in the diaspora. In the book’s introduction, Tabios specifically calls out the Marcos dictatorship for the harms caused to Filipinos who fled the country to escape the violence and turmoil of the Martial Law era (1972-1986), as well as the torment endured by millions of Filipinos who had little choice but stay behind. The author was a child when her family escaped the talons of martial law under the Marcos regime. She draws a link between the damages wrought by the Marcos regime to the renewed clamor for strongman-style leadership that led to the election of Rodrigo Duterte in 2016. The dictator not only ransacked the treasury, he also drove away the collective memory about the painful truths of those difficult and repressive years.

Read the full review